Covariates in the detection function

Distance for Windows exercise

This exercise consists of two datasets of increasing difficulty. They take you deeper into the heart of understanding multiple covariates. Feel free to complete as many as you like.

Passerine data from T. A. Marques et al. (2007)

The data from the Auk paper by (T. A. Marques et al., 2007) is also available. It is zipped as the project fTAMAUK07.zip.

The survey information in this project is from seven surveys carried out in Hawaii 1992-1995 of the Hawaiʻi ʻamakihi (Chlorodrepanis virens). In addition to standard distance sampling information, the project contains four observation-level covariates:

- initials of the observation making the detection (factor),

- hours after sunrise (continuous) and

- minutes after sunrise (continuous).

There is no area measure associated with the surveys so abundance estimates will not be produced. Construct models with the covariates to build the best model for these data.

Dolphin Sightings Data

In this exercise there are several potential covariates and no ‘right’ answers. Begin your investigation by downloading the archived Distance for Windows project Dolphin.zip and opening it using the Distance for Windows software.

Reviewing the data

In this example we have a sample of eastern tropical Pacific (ETP) offshore spotted dolphin sightings data, collected by observers placed on board tuna vessels (the data were kindly made available to us by the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission – IATTC). A full description of the analysis of these data can be found in F. F. C. Marques & Buckland (2003). In the ETP, schools of yellow fin tuna commonly associate with schools of certain species of dolphins, and so vessels fishing for tuna often search for dolphins in the hopes of also locating tuna. For each school detected by the tuna vessels, the observer records the species, sighting angle and distance (later converted to perpendicular distance and truncated at 5 nautical miles), school size, and a number of covariates associated with each detected school. Many of these covariates potentially affect the detection function, as they reflect how the search was being carried out.

A variety of search methods are used to find the dolphins, but currently the most commonly used are 20x binoculars from the crow’s nest, 20x binoculars from another location on the vessel, from a helicopter, or through “bird radar” (high power radars which are able to detect seabirds flying above the dolphin schools). In the example dataset these are coded as 0, 2, 3, and 5, respectively. Some of these methods may have a wider range of search than the others, and so it is possible that the effective strip width varies according to the method being used.

For each sighting the initial cue type is recorded. This may be birds flying above the school, splashes on the water, floating objects such as logs, or some other unspecified cue. In the example they have been coded as 1, 2, 4 and 3, respectively.

Another covariate that potentially affects the detection function is sea state, as measured by Beaufort. In rougher conditions (i.e. higher Beaufort levels), visibility and/or detectability may be reduced. For this example, Beaufort levels are grouped into two categories, the first including Beaufort values ranging from 0 to 2 (coded as 1) and the second containing values from 3 to 5 (coded as 2).

The sample data encompasses sightings made over a three month period: June, July and August (months 6, 7 and 8, respectively).

Begin by extracting and opening the project from the archive Dolphin.zip. Once it is open, you will see the Project Browser, from which you can have a look at the data (Data tab).

Analysis of Dolphin Sightings data

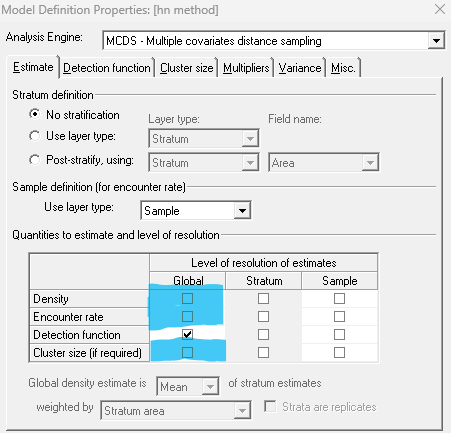

The data in the project is only a portion of the data for the survey; for example there is only a single transect depicted and it is of unknown length. Nor is the size of the study area provided. Because of this, estimates of abundance and density will not be meaningful. The focus of the exercise is upon exploring covariates in the detection function. Consequently, it might be simplest to specify that estimates of density and abundance are not of interest; this is done using the configuration of Model Definition Properties shown in the screen shot at right.

The data in the project is only a portion of the data for the survey; for example there is only a single transect depicted and it is of unknown length. Nor is the size of the study area provided. Because of this, estimates of abundance and density will not be meaningful. The focus of the exercise is upon exploring covariates in the detection function. Consequently, it might be simplest to specify that estimates of density and abundance are not of interest; this is done using the configuration of Model Definition Properties shown in the screen shot at right.

Start by running a set of conventional distance analyses. Are there any problems in the data and if so how might you mitigate them? (Hint – check out the q-q plot, and also try dividing the data into a large number of intervals in the Model Definition | Detection Function | Diagnostics.)

Because of a surplus of detections at perpendicular distance 0, it is best to convert the distances to binned distances, using say, 15 equal width bins before fitting models to the data.

As there are a number of potential covariates to be used in this example, try fitting models with different covariates and combinations of the covariates. All of the covariates in this example are factor covariates except cluster size. We suggest that you not explore detection functions with cluster size, simply because we will revisit this data set again in the module where we discuss cluster size.

Keep in mind that this is a large dataset (> 1000 observations), and hence estimation may take a while, particularly if you are allowing several adjustment terms to be fitted. It will be generally more efficient to start fitting models without any adjustment terms, and then adding one at a time if appropriate. Consider also whether to standardize by w or by σ (or try both).

You will likely end up with quite a few models, so think about how you are going to name and organize them in the Project Browser (for analyses) and Analysis Components window (for model definitions).

- Model convergence problems arise when using the hazard rate model particularly in association with the

sea statecovariate,monthcovariate and thecue typecovariate. - Run some of these models and see if you can diagnose the source of these problems.

- To circumvent the problems, perhaps restrict your candidate model set to the half normal key function along with covariates.